Our Thermal Envelope Theory: Get it Right the First Time

I am the man with a plan, the design and the drawings. I’m not the one on the front lines, at job sites where frost builds up at the base of a wall in a 175,000-square-foot refrigerated warehouse. I wouldn’t be the first one to notice the presence of moisture in the form of ice crystals forming below refrigeration units or water pooling along the floors. But you can bet our superintendents and project managers would notice any such aberrations right away. It’s my job to make certain that they do not.

If you hadn’t surmised, we’re talking about what can happen if there is a leak in the thermal envelope of a building (i.e., the walls, doors, windows, floor and roof/ceiling that separate areas of differing desired temperatures). This is typically considered to be the exterior perimeter of a building, but can also be applied to adjacent interior rooms/spaces that have different operating temperatures. The thermal envelope plays a critical role in the energy efficiency of a building and is a major factor in the function of a space.

The frost and moisture can cause a plethora of problems ranging from product contamination and increased utility bills to aesthetic damage. Worker safety hazards are the most serious potential consequence of ice or moisture forming on concrete floors. There are steps you can take to correct the problem, of course, such as using smoke tests and thermal imaging to identify exactly where the weak spot is and repair it, but I prefer a more proactive approach.

To mitigate possible problems, I would encourage building owners to work with design professionals who will incorporate measures to create a building envelope that is vapor tight. Here are key issues to consider.

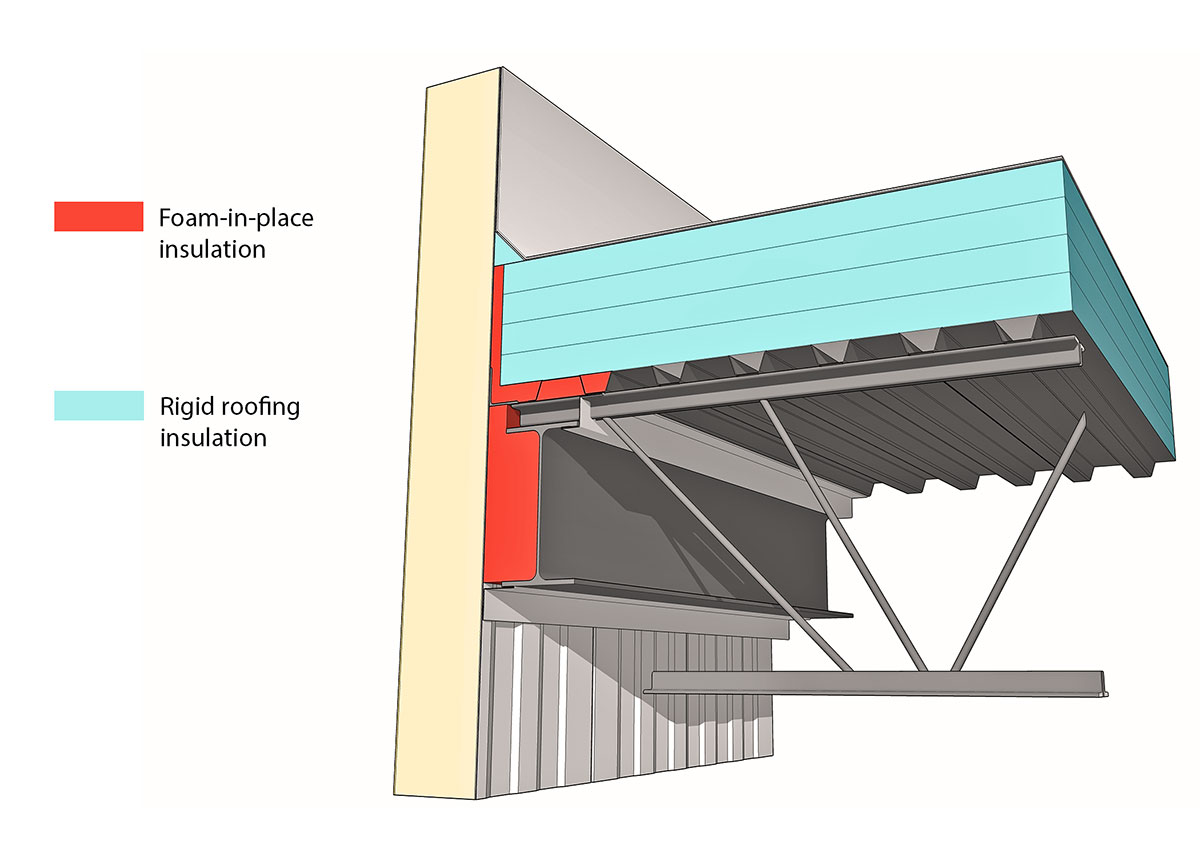

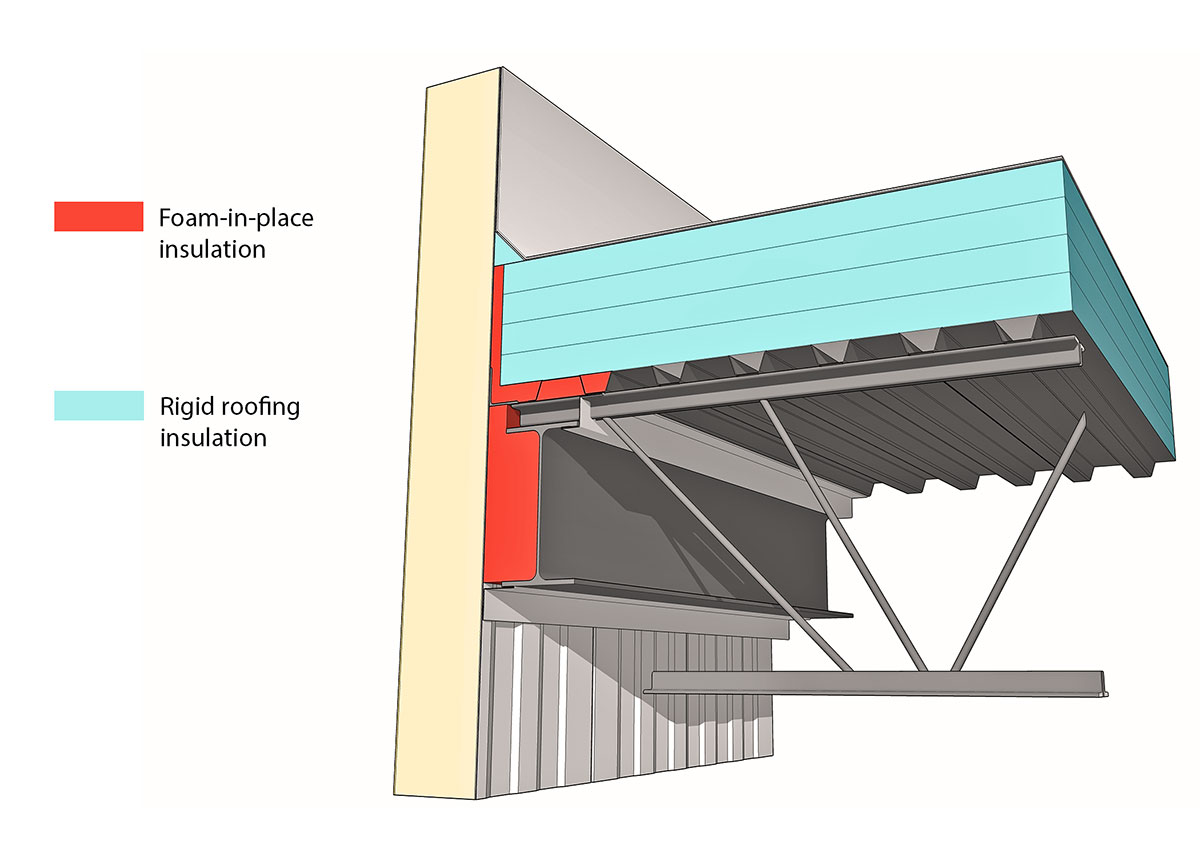

- Choose materials wisely. The materials we construct our buildings with play a role in the transfer of heat from one space to another and it is important that we understand the properties of these materials to properly design and build. Metals and concrete are conductors of heat. When building with these materials, it is necessary to create a thermal break (in Insulated Metal Panels (IMP), a continuous cut in the metal skin layer, or a complete break in concrete) to keep heat from transferring into, or out of the building/space being designed.

- Examine facility layout. If you don’t organize the rooms in your buildings from warmest to coldest, adjacent spaces with large differences in temperature have a higher potential to create condensation problems and will also reduce the building’s energy efficiency. The number and placement of doors also create good workflow within the space and minimize temperature migration.

- Assess meeting places. When planning thermal breaks, look at how the wall meets both the floor and roof structure, as well as any penetrations that may be present in the space. Additional insulation may be required, or in some cases it may be necessary to have completely separate structures from space to space. The foam-in-place, illustrated in red in the diagram above, is a key component of sealing the thermal envelope and keeping heat from transferring and creating condensation within the building.

When dealing with a building’s thermal envelope, it is always worth the extra time to consider all aspects and details of how your facility will be put together before construction starts. This will save everyone– from the designers, contractors and owner– from dealing with costly problems that may result in shutdowns to the owner’s operation.