The Power of Resilient Design

There is a concept in architecture that continually speaks to me. I’ve seen its absence create constraints, added costs and sometimes an unnecessary plan for new construction or demolition. Its presence, on the other hand, reimagines the built environment as dynamic, easily and proficiently adapting to change. I’m talking about resilient design, a strategy that allows food and industrial facility owners to react to the shifting requirements of a building and its occupants — faster, cheaper and more sustainably.

Resilient — from the Latin verb resilire — best describes the spaces that are designed to accommodate client growth. In other words, resilient facilities are adaptable (meeting the changing needs of that area or building) and durable (the materiality and construction techniques that provide long-lasting solutions). I also draw inspiration from a closely related concept called ‘flexible architecture,’ which prioritizes building mobility, movability and multifunctionality.

In this article, I’d like to share some different perspectives about resilient design and flexible architecture, as well as three real-world examples that illustrate how it can work for you.

What is Flexible Architecture?

The term “flexible architecture” was popularized in the book Flexible: Architecture that Responds to Change by Robert Kronenburg.He says that the majority of architecture is static, unlike the natural world which adapts to its surroundings. He studied the idea that buildings should be able to respond to shifting needs and adjust to new uses. From the tents and yurts of nomadic tribes to the growth of the pre-fabrication industry, the author succinctly describes the role of change in architecture and its contemporary relevance.

Similarly, I really like the way ArchDaily explored the idea of incorporating uncertainty into architecture. The author provides examples where architects have experimented with creating a framework that can accommodate a variety of scenarios, evolving with time and through the input of users. Because there have been many changes in our society during the past couple of years, it’s even more important to think about how we can design for change.

Many of the companies I’ve worked with have like concerns.

Our clients want to extend the lifecycle of their facilities, use materials/strategies that will lessen impact on the environment, and ensure employee safety and satisfaction.

Spaces that serve their purpose for longer periods of time require fewer renovations, thus minimizing debris going to landfills and downtime or workflow adaptations resulting from construction. Essential expansions can be executed quickly due to planning efforts and techniques implemented in prior design work. Finally, resilient design can promote employee satisfaction and productivity with customized workspaces that can shift as easily as the needs of the employees do.

Resilient Design in Practice

Resilient design incorporates both flexible and durable design that considers spatial relationships, materiality and construction techniques. I like to think of these ideas on both a big-picture, macro scale and at a smaller, micro level. Macro issues comprise site planning, site logistics, utility location, campus organization and building layout. Site context and building usage play a vital role in determining building orientation and maximizing facility efficiency, all while allowing sustainable growth and change. Micro elements include natural lighting, material selection, flexible furniture and building systems, and construction methods that accommodate change.

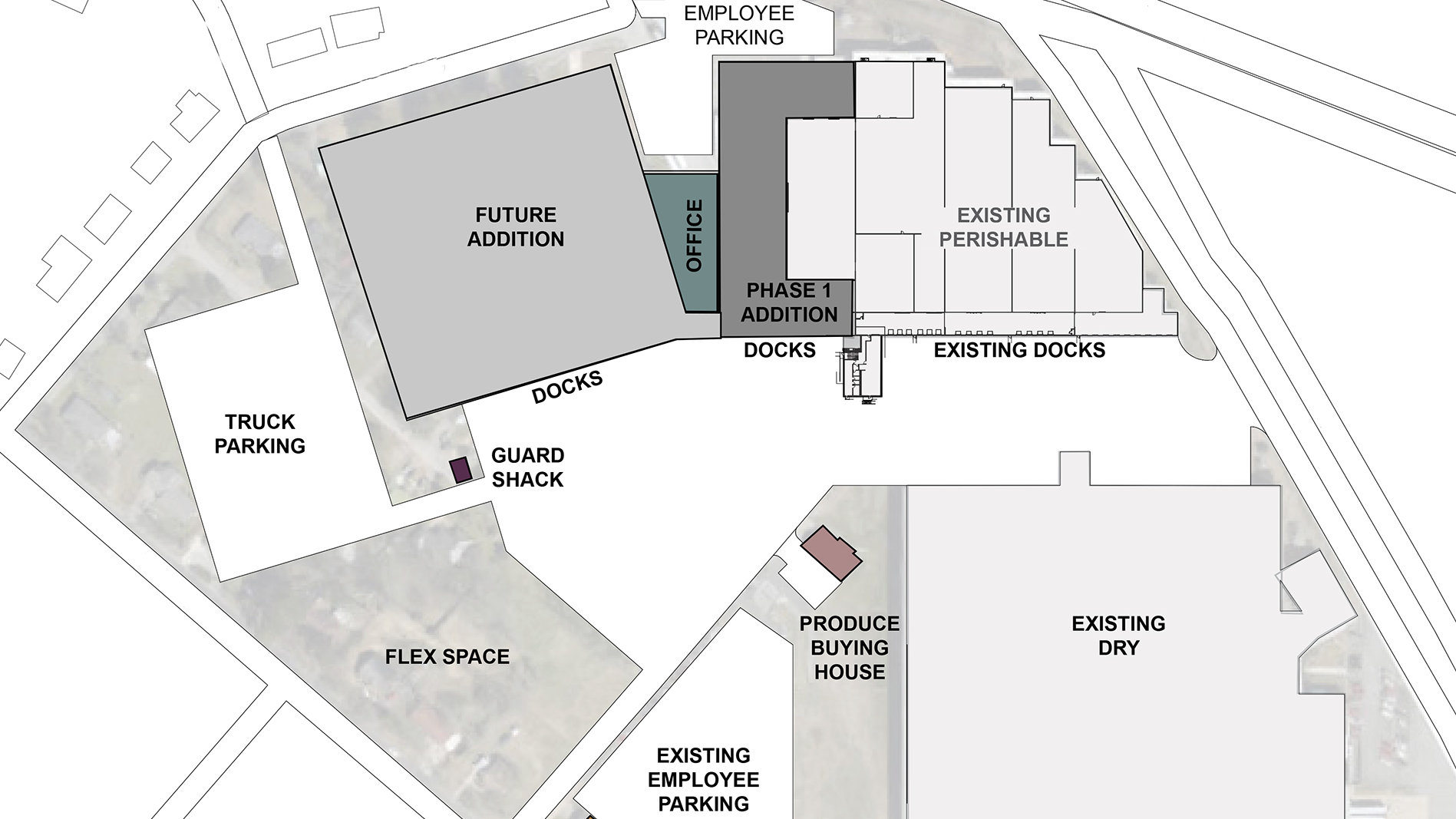

Example 1 (Macro): Take my work with a Southeast-based grocery retailer, for instance. Before beginning design and construction of a 33,000-sf distribution center expansion, they communicated their struggles with an inefficient facility layout. The master planning exercise we completed assisted us in the design of a Phase 1 addition, which is situated specifically to meet a variety of needs of their expanding customer base now and going forward.

We made our recommendations based on extensive analysis of the site, including topography, drainage and vehicular access. Ultimately, our resilient design incorporated valuable warehouse space to meet current needs, limited environmental disturbance, reworked site access, minimized unnecessary demolition and cut costs. This strategy also helped us plan for future expansion and easy manipulation to address changing needs. In a nutshell, this is the beauty of proactive design versus reactive design.

Example 2 (Macro): During our first expansion project at Cheney Brothers Inc.’s Statesville facility, the owner expressed interest in the option for an additional freezer.

With space at premium, our team developed a plan to build in flexibility to a 29,000-sf meat cooler so that it could be converted to a freezer in the future.

Accomplishing this formidable task in short order necessitated extra insulation under the slab, use of additional thermal breaks around the space and mechanical equipment to support the required temperature range. Not only would this strategy permit the client to easily transform that space, but they would also be able to split the room to function as both a cooler and a freezer. Planning for uncertainty is what was needed and that’s what we delivered.

Example 3 (Micro): Our Design-Build teams consistently perform many interior renovations for ALDI USA distribution centers around the country. Since warehouse space is critical for operations, and limiting the area dedicated to such processes impacts revenue and efficiency, we continually look for ways to minimize impact on those areas. One key strategy is to develop a dual-function space in what may have originally only served as a breakroom for employees.

Our flexible design, which focuses on A/V walls, lighting in a grid ceiling, acoustics, and movable furniture, can transform the space into a meeting/presentation space for corporate events, and back again. The careful thought that goes into development of this space allows it to be used at high efficiency and minimizes additional construction needed for multiple uses. These strategies support clients by increasing the lifecycle of the building and reducing future construction materials and costs. It’s important to note that incorporating resilient design early will maximize these benefits.

Adapting to Change

The Environmental Protection Agency reports that more than 75 percent of all construction waste from wood, drywall, asphalt, shingles, bricks and clay tiles end up in landfills. By introducing flexible design into our built environment, we can assist our clients in decreasing that construction waste, promoting building longevity and efficiency, and improving employee well-being.

We as a nation spend most of our time in buildings and expect a lot from them. Therefore, it makes sense to approach their design with resiliency, plan for future improvement and minimize impact from change.

Charles Darwin stated, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.”